Witch Hunt 1649

Witch hunting in Scotland

In June 1563, the Scottish Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act, calling for any who used ‘Witchcraftis, Sorsarie and Necromancie’ to be put to death. It was not repealed until 1736, by which time several thousand people had appeared at local or central courts on charges of magical malpractice and covenants with Satan. The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft catalogues 3,837 accusations, about 84% against women. Possibly around two thirds of accused individuals were executed.

Witch trials took place most frequently in Scotland’s central belt, with about a third of accused witches coming from the Lothians. The first large-scale trials took place in the 1590s, spurred by the involvement of King James VI, who suspected diabolic conspiracies against his rule. There were further waves of witch hunting in 1628-30, 1649 and 1661-2. By the late 17th century the witch hunts were waning, as lawyers and judges became increasingly sceptical about how witchcraft could be evidenced. The last prosecution took place in 1727.

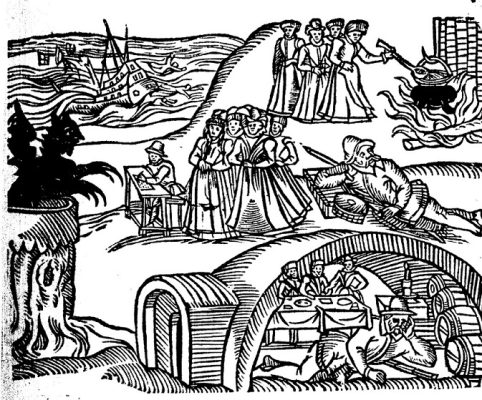

An image from Newes from Scotland, a pamphlet printed in London in 1591. It depicts witches brewing up storms, and attending a service preached by the Devil.

The Scottish witch hunts were relatively severe; Scotland may have executed around ten times as many accused witches per head of the population as England. Brian Levack has outlined three primary legal reasons for this difference. While Scottish witch trials were often conducted by local elites with little or no legal training, England usually tried accused witches in assize courts, where centrally appointed judges directed affairs. Torture was more widely used to force confessions in Scotland, despite theoretically being illegal except by special warrant from the privy council. By the terms of England’s witchcraft act, some charges of witchcraft were punishable by imprisonment, while Scotland prescribed execution in every case (though this was not always carried out in practice).

In addition, the Scottish religious and secular authorities constructed a powerful narrative framing witch hunting as a form of social progress. Witches were heretics who worked with the Devil to bring evil upon the land, and witch hunting was part of a broader endeavour to mould Protestant Scotland into a ‘godly state’. All the same, witch hunting did not just come from ‘above’. Most prosecutions began with accusations by neighbours, which often stemmed from quarrels. People testified in courtrooms that hostile neighbours had cursed them, or perhaps attacked them with harmful magic (maleficia).

Making sense of witch hunting requires us to empathise not only with the accused, but also their accusers. The story of witch hunting is in part a story about misogyny, and about a church and state keen to exert authority over the population. But it is also a story about men and women who believed that their community was vulernable to diabolic attacks, and feared that the lure of power or wealth might corrupt the hearts of their neighbours. The witch trials were an evil that emerged from a particular cultural context. They also reflect the enduring human capacity to make enemies of the innocent.

For further reading on Scottish witchcraft, see the reading lists under the Resources tab.

The 1649 witch hunt

The 1638 Covenanting Revolution threw Scotland into turmoil. In a bid to secure a Presbyterian church free from monarchical interference, the Covenanters took arms against King Charles I’s forces. Meanwhile, Charles was becoming embroiled in a power struggle with his parliament. Over the subsequent decade, England, Scotland and Ireland were drawn into the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a bloody negotiation about the extent of the royal prerogative. In January 1649, England’s Rump Parliament executed Charles I; England subsequently became a republic. Scotland fell temporarily under the control of the most radical Covenanting faction, the Kirk Party. The Kirk Party forged an agreement with Charles II and recognised him as king of Scotland in 1651, but after military defeat at the hands of Oliver Cromwell, Scotland was annexed into the English Commonwealth.

Detail from image of Charles I by Wenceslaus Hollar, 1644

The 1640s was thus a decade of profound political instability. It also saw the resurgence of plague; a furious eruption in Edinburgh in 1645 may have killed as much as half of the population, and outbreaks continued until the end of the decade. The weather was bad, too. Cold winters and heavy rainfall disrupted agricultural output, and in 1649 there was famine in parts of the country. Interpreting these misfortunes as the punishments of an angry God, the Kirk Party resolved to cleanse Scottish society of ungodly elements. In early 1649 parliament passed a raft of acts stamping down on sexual misbehaviour, blasphemy, swearing, drunkenness and other behaviours judged impious. Amid this campaign against sinfulness, witchcraft fell under fresh scrutiny: a new act, passed on 1 February 1649, extended the 1563 act to cover ‘whatsoever persone or persons shall consult with devillis or familiar spirits’.

In this context, witch hunting gathered pace. From 1649 to 1650, perhaps around 800 people were accused of witchcraft, of whom as many as a half may have come from the Lothian area. Haddington saw particularly high numbers of trials. Sometimes Scottish witch trials were held centrally at Edinburgh’s justiciary court, but this does not seem to have happened in 1649-50. Commissions were granted by the committee of estates, which was appointed by parliament (prior to the revolution this job had belonged to the privy council, appointed by the king). Trials were then arranged locally, which meant high execution rates. While the central government was keen to stamp out sin across the land, the big push for further prosecutions came from localities; the committee of estates often frustrated local authorities by being slow to grant commissions, and some trials went ahead without official authority. The witch hunt was derailed by the arrival of Cromwellian troops, which presented parliament and people with a more immediately pressing enemy.

1654 map of Lothian and Fife, from John Blaeu’s Atlas Maior.

For more on the 1649-50 witch hunt, see especially Paula Hughes, ‘Witch-Hunting in Scotland, 1649-1650’, 85-102 in Julian Goodare (ed.), Scottish Witches and Witch-Hunters (Basingstoke, 2013).

The Dregs of Days

The Dregs of Days offers a window into community life in an East Lothian village. It aims to show some of the hardships that might generate division, and explore the ways in which people might antagonise the church or their neighbours. It also looks at the accusations levelled against supposed witches. Some of these accusations – e.g. those about people falling ill, or food and drink being stolen – might have originated in neighbourhood tensions. Claims of contact with the Devil were typically introduced by elite interrogators after suspicion had already fallen on the accused.

The drop-down menu below explores how different aspects of the game reflect, or do not reflect, historical realities.

We included allies to avoid making the game entirely dog-eat-dog. But early modern people also collaborated with those beyond their family groups! By giving players only one ally and setting them against everyone else at the table, The Dregs of Days overstates the degree of hostility in a normal neighbourhood.

In designing Asset cards, we aimed to include items that 17th-century households might conceivably own. Historical evidence is limited; there are few surviving inventories from normal Scottish households. (The English evidence is much richer.) But it is clear that compared to modern-day society, people owned very little. The average Scottish household was small and sparsely furnished.

We omitted a few basics – characters are assumed to have a dwelling of some kind and some clothing. And some of the assets in the game would be much more commonly owned than others. Almost every rural family would have a cow. Pigs were much rarer, and often banned for the damage they caused. A milk pail was another essential, whereas querns were owned only on the sly, grain-grinding being the prerogative of the local miller. Every respectable family was supposed to own a Bible, and the church would sometimes distribute them. However, the few surviving Scottish inventories suggest that this was a luxury item in practice.

We sought to reflect which assets in each category would be most and least valuable, but this is necessarily approximate. A byre was naturally more valuable than an ale cask! Some assets could conceivably belong to more than one category. A sieve was used for straining milk during cheese-making, but also to sort grain. Kilns were used to dry grain, but also to make lime.

The selection of assets a player comes to hold in an average game may not make sense – fishing bait was not much use without other fishing gear, for instance! In reality, asset ownership would be gendered; drop spindles were more usually used by women, fishing spears by men. The categories are somewhat artificial; ‘livestock’ were also part of ‘farming’. Asset card effects were chosen for gameplay purposes, and are not necessarily logical.

The Dregs of Days contains 7 characters, of whom 5 are female. This was intended to approximate the proportion of women relative to men who were accused of witchcraft. We didn’t specify much about characters because we wanted players to build up their own impression of their characters based on in-game events and asset purchases, but they are intended to represent the demographic most usually accused: people from the middling tiers of society, who might have a small amount of land, some possessions and some means of subsistence.

Fate cards explore some of the challenges facing early modern people. Many are inspired by evidence from church or court records. For gameplay purposes, Fate cards are negative (we found that including even a few positive ones made the game too unbalanced). In reality, of course, positive things happened to people as well! A game about witch hunting necessarily offers a bleak view, but early modern communities also enjoyed festivals, songs, stories, games and celebrations of various kinds.

Welfare in the game represents physical, mental and financial wellbeing, while reputation is about players’ standing both with neighbours and with the church. We tried to show that it could be difficult to maintain a balance; attending solely to one’s personal wellbeing might result in more strained relations with neighbours. We also tried to make welfare and reputation losses from Fate cards reasonably logical, but they are naturally gamified to a degree, and it is probably rather too easy to die or get banished.

Typically, those who were initially accused of witchcraft within a community were individuals who had built up a bad reputation through quarrels or other disagreements with neighbours. As trials progressed, the net was often cast wider, as accused witches named supposed accomplices. Many games will include this sort of snowballing effect, with several additional trials rapidly following the first one. However, we didn’t find a way to represent the specific circumstances that caused particular individuals to first be accused, besides the implications of neighbourly tensions that generally arise from Fate cards. (We experimented with triggering a witch trial when a player’s reputation fell below a certain point, but didn’t find a system that worked well from a gameplay perspective.)

The accusations on Black Mark cards are drawn from real trials, though people would most likely have more than three raised against them. We tried to differentiate between the kinds of accusations that generally came from (likely illiterate) neighbours, and the kinds that were introduced by educated men during the interrogation process, though of course this distinction was not always perfectly clean. Most accusations were about harmful magic, rather than liaisons with the Devil.

For gameplay reasons, we’ve increased players’ chances of survival (we found that playtesters didn’t like dying without recourse). We allow players to mount a defence, which means that we’ve given them more agency than accused witches generally had in local trials. Accused witches would not usually have legal representation unless they were wealthy and/or tried in a central court, so their participation in their own trials was generally limited to entering a plea. Usually accused witches would already have confessed prior to the trial – it was common for the central authorities to require a confession before they granted a commission for a trial, though this rule was circumvented on occasion. Pleas would often take the form of the accused confirming their confession, though sometimes accused witches did attempt to retract their confessions. For further information, see the details on trials under the Resources tab.

The rule that one can’t be re-tried after acquittal is drawn from early modern Scots law, which typically would not permit people to be tried multiple times for the same crime. People might be tried multiple times when new charges were brought, though. For example, Janet Cook was acquitted of witchcraft in 1661-2, but new charges were brought and a retrial took place a month later, at which she was found guilty.

Lying Lips

Lying Lips reflects the significance of words in driving forwards the witch hunts. When investigating community conflict, the kirk session (local church governing body) often found itself meting out punishments for scolding or slander – both offences particularly associated with women. In the context of witch trials, these altercations took on new significance. Verbal curses might be evidence of magical practice. Calling a rival a witch might tarnish her reputation, though she might succeed in reframing the accusation as malicious slander. People also gossiped, spreading news of other witch hunts and sharing suspicions about unlikeable neighbours.

In Lying Lips, players trade using the assets from The Dregs of Days (discussed above). This is artificial in some respects. Payment in kind for goods or services was common, people would more usually trade livestock or consumable goods than possessions such as kilns! But the trading portion of the game does reflect how communities were bound together, with neighbours economically dependent on one another.

The Rumour card represents the spread of gossip within a close-knit community. The Rumour card is powerful; when you have it in hand you are controlling the village narrative, and can potentially win the second stage of the game. But gossipers, slanderers and ‘back-biters’ also made themselves unpopular, and there is a risk that your neighbours will turn against you. When the commissioners and jurors seek to identify the player holding the Rumour card, they are not identifying ‘the witch’, but rather the argumentative player perhaps most likely to be accused of witchcraft in an early modern community.

In the second stage of Lying Lips, players take on characters in a witch trial, with the most successful character from the first stage becoming the commissioner. Roles are intended to show the key figures in the courtroom, though a real (local) witch trial would involve a group of commissioners and a jury of fifteen, as well as administrators. We gave the commissioner the job of reading out dittays and death sentences, though these jobs in reality fell to the court clerk and the dempster respectively. Witnesses might be present in person, or might give evidence through written dispositions. Usually the lead commissioner acted as the prosecutor, and the accused did not have legal representation, though sometimes professional lawyers were involved. Usually the accused had already confessed, though this might be retracted in court. For further information, see the details on trials under the Resources tab.